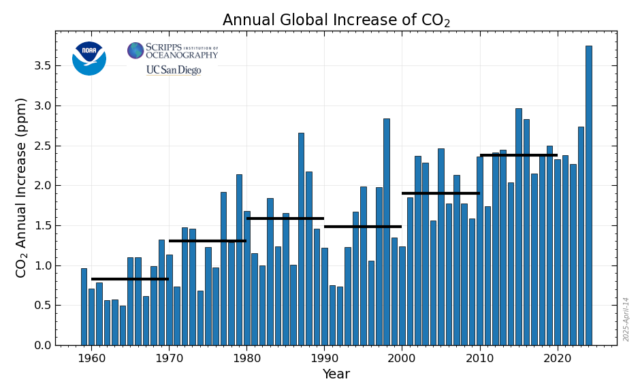

The unprecedented increase of atmospheric CO2 is just one of several red lights flashing on the climate dashboard.

This graph shows the annual mean growth rates of carbon dioxide, with decadal averages shown as horizontal lines across the bars.

The largest spike shown in 2024 represents an annual increase of 3.75 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the air.

It is the largest yearly increase since measurements started in the 1950s.

Credit: NOAA Others include the 20232024 spike of the global average surface temperature, which has also not been fully explained, and the fact that Earths average temperature has stayed above a 2.7 Fahrenheit temperature target set by the Paris Agreement for 20 of the last 21 months.

Additionally, the combined sea ice extent in both polar regions has dropped to record or near-record lows the last few years, which means Earth is losing some of its biggest heat shields.In recent years, NOAA publicized the annual updates to the global greenhouse gas index with press releases and explanatory articles on its website, and the agency was set to do the same this year, said Tom Di Liberto, a former NOAA public affairs specialist who was fired by the Trump administration in late February along with hundreds of other NOAA staffers.That article was written, and then it was taken down by the current political communications leader of NOAA because it would not make the administration happy, he said.

NOAA is likely to still be doing the work internally, but its very unlikely you will see stuff coming out of NOAA like you had in the past.NOAA did not provide answers to Inside Climate News questions about this years increase.Climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, said the CO2 spike may reflect the post-COVID emissions bounce as economies restarted after lockdowns, but he said the general expectation is that emissions will start to plateau this year, largely driven by decarbonization by China and other countries.Ive seen the claim made that decreased uptake by natural sinks and wildfire emissions might have played a role, he said.

But my view is that this may be a misinterpretation of the fleeting impacts of extended, major El Nio events like 20232024.James Hansen, an adjunct professor at Columbia Universitys Earth Institute and director of the Program on Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions, said the 2024 CO2 increase is not surprising, given continued record-high emissions from fossil fuels, as well as the record-warm oceans.Similar increases have occurred with lesser emissions, but stronger El Nios, he said.

Its not all gloom and doom.

The airborne fraction of emissions has actually trended downward over the past several decades, so once we begin to reduce emissions, we should be able to get the growth rate of CO2 to decline.

6

6