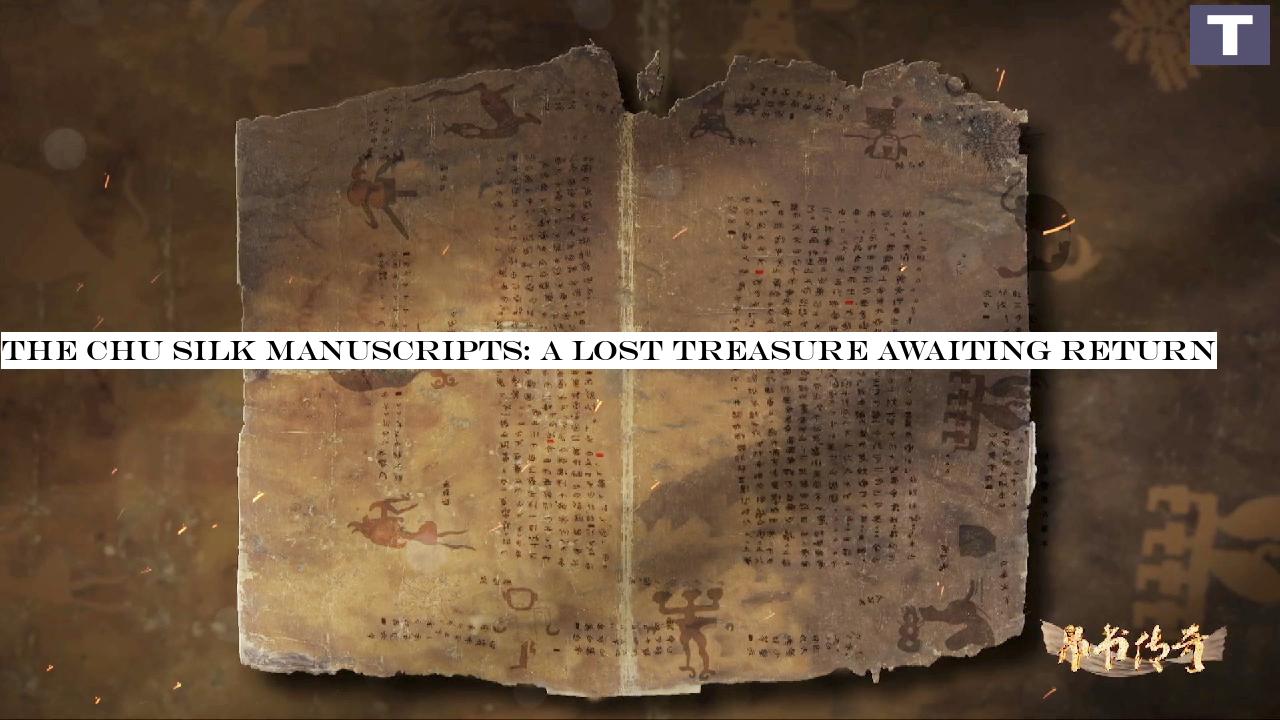

Older than the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Chu Silk Manuscripts holding a Chinese creation myth have been separated from their homeland for almost 80 years.

What are the manuscripts? Why are they so significant? And how were they unscrupulously taken to the United States? Find out more!Before the sun and moon existed, four spirits divided the year into four seasons through a relay of footsteps.

When the heavenly bodies emerged, they brought chaos and imbalance.

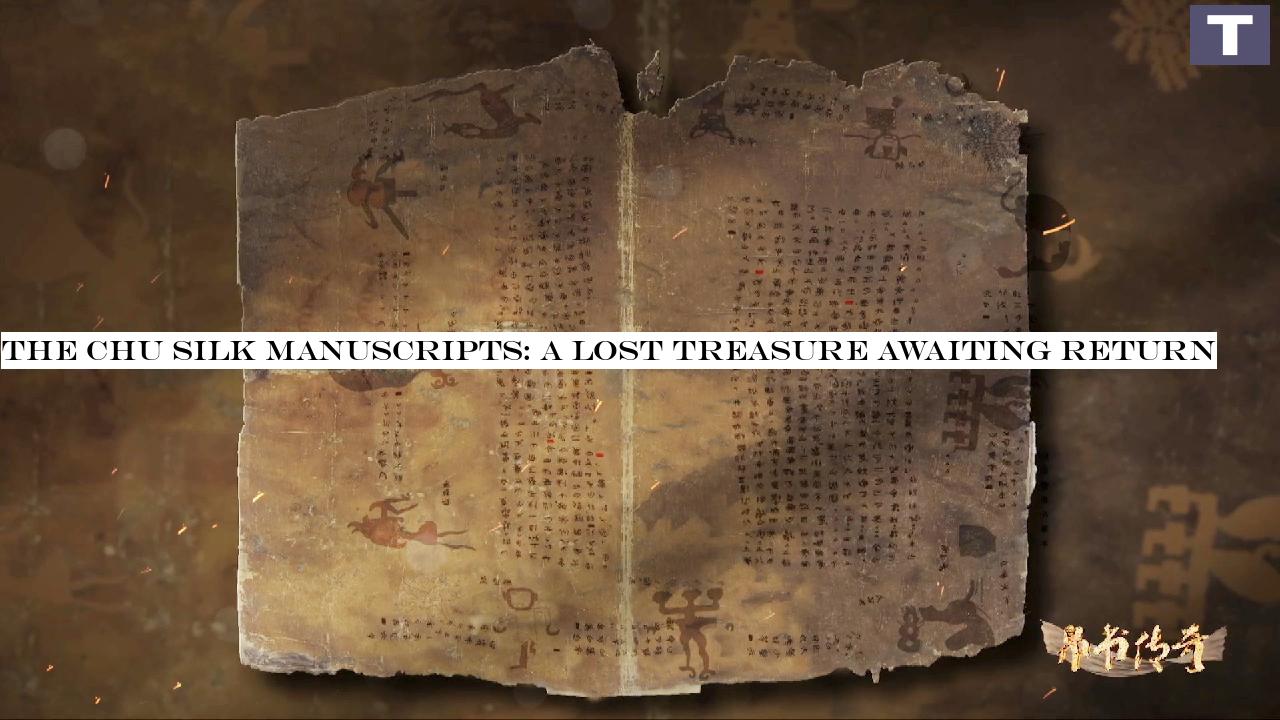

To restore cosmic order, the four spirits raised colossal trees to hold up the sky, giving rise to spring, summer, autumn, and winter.This is part of an early Chinese creation myth preserved in the Chu Silk Manuscripts, an ancient astrological and astronomical text from around 300 B.C., unearthed at Zidanku (a place name that literally means "bullet storehouse") in Changsha, Hunan Province.

They are the only known silk manuscripts from China's Warring States period, but have been lost overseas for nearly 80 years after being unscrupulously taken to the United States in 1946.Discovered in 1942 in a Chu State tomb, the manuscript later to become known as the Four Seasons Almanac, along with some fragments, was purchased and restored by local antiquarian Cai Jixiang, who recognized the rarity of the manuscript and believed it to have been used by ancient people when praying to deities.

With both texts and illustrations, the manuscript presents an early form of the Chinese almanac tradition.

Measuring 47 by 38 centimeters, it is divided into three parts: a long inner text on the theme of the "year," a shorter inner text narrating a cosmic creation myth and the establishment of the four seasons, and a border of twelve zoomorphic month gods and four symbolic trees, each corresponding to a season.In 1946, Cai brought the manuscripts to Shanghai to seek infrared imaging that could help decipher their blurred characters.

There, John Hadley Cox, an American antiquarian, tricked Cai into handing over the manuscripts, smuggling them to the United States.

Cai spent decades trying to get the manuscripts back but failed.

In 1965, the Four Seasons Almanac was purchased by Arthur M.

Sackler, an American philanthropist.

Today, the Chu Silk Manuscripts the Four Seasons Almanac and other fragments including another type of almanac and a divination manual for attack and defense are housed at the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C., along with the original bamboo storage case.The Chu Silk Manuscripts are one of only two complete classical silk manuscripts ever unearthed the other being the Mawangdui Silk Texts dated to 168 B.C..

The Chu Silk Manuscripts represent the earliest known example of shushu (numerals and skills) literature, a major category of ancient Chinese writings that encompasses astronomy, calendrical science, and divination.

The manuscripts' creation myth, unknown before their discovery, also reshapes the understanding of early Chinese cosmology.In comparison to the famed Dead Sea Scrolls, which date to around 170 B.C.

and were discovered in 1947, the Chu Silk Manuscripts are even older and were found earlier.

Their significance has increasingly been recognized internationally.

Before his death, Arthur M.

Sackler himself expressed a wish to return the manuscript he purchased to China."Dr.

Sackler understood what the significance of the Silk Manuscript was," said Lothar von Falkenhausen, Distinguished Professor of Chinese Archaeology and Art History at UCLA.

"He realized that something this important should not be kept outside of the country of origin.

I hope very strongly that all the Silk Manuscripts will be speedily returned to China, where they belong."During a renewed excavation at Zidanku in 1973, archaeologists uncovered a beautifully crafted silk painting, depicting a man riding a dragon.

Scholars hope that one day, the manuscripts and other relics from the Chu tomb at Zidanku will be reunited in Hunan, allowing the full richness and achievements of the Chu civilization to be properly displayed.The Chu Silk Manuscripts stand not only as a treasure of ancient Chinese culture, but also as a symbol of the many cultural relics scattered across the world.

The hope for their return echoes a broader desire for the reunification of China's lost heritage.

19

19